| |

| The topic of this essay is furniture within the field of artistic practice. In particular the kind of furniture associated with the positioning of the body i.e. couches, beds, chairs more than tables and bookcases. This text is a meditation on some possibilities of furniture. The thoughts presented regard my own hopeful expectations drawn for an artistic practice rather than conclusions or judgement about certain works. |

| |

| When thinking about furniture it becomes obvious how insufficient the term “viewer” really is. The “viewer” is not a passive spectator but an active user of the piece. This goes for art in general too if you are not to miss an essential part of its potential though the using of the piece is not necessarily as concrete as sitting on it. Furthermore, one needs to do one’s own sitting or using of the piece. The generalized viewer or user is in each case a specific one. When interfacing with a piece of furniture a person situated differently might thus experience the same piece differently. In a concrete sense whether the furniture is too small or too tall varies from giant to dwarf. In an abstract sense what the piece includes on the levels of form and content is an open question. In other words, furniture is bidding the autonomous art piece a farewell. |

| |

| Taking a rest is, at least at some point during the day, a concern of and a benefit to any‘body’ regardless of the quality of one’s interest in art. A piece of furniture can be approached on a common level of service no matter how you are situated and is in that way “democratic.” Nevertheless, furniture clearly prescribes a way of positioning one’s body and thus a behaviour. An example is the public benches designed specifically not to sleep on. Some bus stops in Denmark feature benches designed only to lean against so that a body cannot get comfortable, its design ensuring a negation of sleep. A circular couch with a circular backrest I encountered in an airport made room for eight, as far as I recall, without any of them facing each other. It provides a private space with the minimum of social contact as everybody would sit as much as possible with the back against everybody else. This brings another piece of furniture to my mind; a two-person couch called a Tête-à-tête [literally head-to-head] from The Victorian Home at The National Museum of Denmark. It is designed so that you would sit next to each other but facing opposite directions. Seen from above the backrest is in the shape of an “s”. This brings the users rather close encouraging intimate conversations. Whispering would be sufficient. |

| |

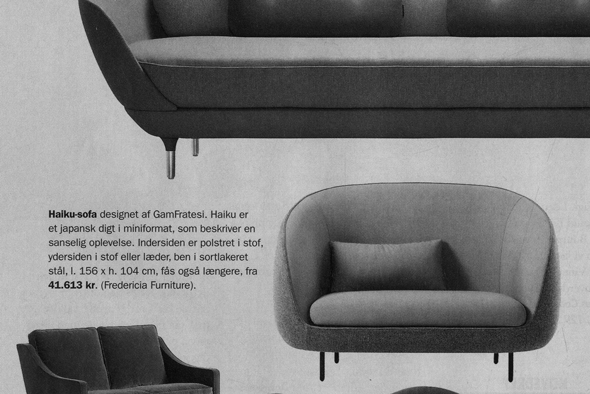

| Close by from where I live a furniture store sells the Haiku-Couch. An add for the couch reads: “Haiku-Couch designed by GamFratesi. Haiku is a Japanese poem in short format describing a sensuous experience. The inside is upholstered by fabric, the outside by fabric or leather, legs in black lacquered steel. l. 156 x h. 104 cm, available as longer, from 41.613 DKK. (Fredericia Furniture).” Besides being an amusing text (a haiku poem is available in a longer version. When an extra two lines of seven syllables each is added you have a tanka) it also presents a compelling notion as the couch appears to be an easy but a bit expensive way to acquire “Japaneseness” (despite the fact that it is custom in Japan to sit directly on the floor or on tatami mats). The notion of associating a mode of being or thinking with the materiality of objects is common. That it is found in advertising seems to be a symptom of a thriving one too. Advertising is quick to assimilate and act but dependent on other fields of activity and interest to develop notions like this. For instance the field of philosophy or artistic practice. |

| |

| Before approaching this relation between thinking and the materiality of objects I will allow myself a short detour. In Uzbekistan there are couches that closely resemble a large double bed only there is a carpet instead of a mattress. Some variations are equipped with a backrest at three sides otherwise it is like the floor has been raised about one and a half feet. Occasionally a small table is placed in the middle and the couch is used for dining but lazing or sprawling works out very well too. Where I am heading is that these pieces of furniture inhere an openness in regards to the positioning of oneself. The number of people intended for the couch and the activity encouraged is not fixed either. Interfacing with this type of couch opens up various ways of behaviour and involvement which makes it furthermore “democratic” compared to the earlier mentioned public benches for instance. It is both providing a service to benefit anybody and leaving the specifications of the service to the specific user. This concerns the material qualities of the couches not necessarily the cultural domain in which they are situated. These Uzbek couches are not meant to be art I am sure but they nevertheless induce an unrestrained behaviour–a quality favourable for art too. |

| |

| Let us consider furniture not only in relation to artistic practice but within artistic practice–as sculptures. These pieces of furniture addressed are based on the same main theme as the classical sculptures of ancient Greece; the body and the positioning of it. Comprehending them as sculptures should thus be relatively straightforward. By being a piece of furniture sculpture is brought into the everyday life. The justifiable reason for the piece existing at all is not its classification as high culture or art but its functionality and serviceability. This makes them somehow easier to engage with as they leave behind the affectation often displayed by art. But if they are sculptures we can still ascribe to them other qualities of sculptures. These potential pieces of furniture I have in mind present ideas. The material qualities of the object such as the form, the tactility, the sensuousness etc. is altogether signifying conceptions. As when politics are found in public benches, display of wealth in interior decoration, “life quality” in the conversation kitchen/ open kitchen [in Danish the concept is called samtalekøkken], and “Japaneseness” in the Haiku-Couch. The means of these objects might be the same of those of sculptures but they lack a crucial openness since they are bound by a determined intention. The single purpose of employing for instance “Japaneseness” within marketing is when all is said and done to sell the couch. If the Haiku-Couch would be considered as art, it would still in my opinion deal with Japanese poetry, living or philosophy in a poor and watered down but conveniently easy digestible way. Being purely an object of commerce or uninterested relaxation is a risk sculptures run too. Whether the piece of furniture displays coherence and efficaciousness within the conception at issue is a question of its material qualities though the significance of the context and the language used in relation to the objects should be emphasized. And even if the furniture as sculpture possess the openness of the Uzbek couch or other coveted qualities an active participation is required. It is to be used if it is to meet its full potential. This is equally true for both the aspect of positioning one’s body and for the aspect of contemplation. |

| |

| The piece of furniture can only be judged on the basis of having an experience with it (not from it). Does the sensuous experience of sitting in fact resemble that of at haiku poem? Does it bring about any new conceptions or elaborate the existing ones? The term experience refers to a process, the interfacing, where the user apply his or her thinking and positioning of the body to the piece of furniture as much as the furniture presents a set of sensuous data and ideas. The materiality of the furniture and the contemplation and activity invested intertwines thus producing an opportunity for either self-realisation or a self-transformation. In the first case the user is confirmed in his or her assumptions. In the latter new knowledge is produced by the user through the interfacing with the piece of furniture confronting him or her with his or her assumptions forcing a self- transformation. This new knowledge need not be objective |

| |

| |

|

| |

| |

| |

|

| |

| |

| |

|

| |

| |

| |

|

| |

| |

| |

|

| |

| |

| |

|

| |

| |