| |

|

| |

| |

| |

“All right, so basically what I’m going to do now is hold your cell phone, and um, I’m going to close my eyes for a couple of minutes and sort of go into a little trance, and I’m gonna ask that you just sit back and relax and have an open mind, and um, I’ll be with you in a couple of minutes...” |

| |

I leaned back on the comfortable leather couch, but I would not relax. I felt as if I were sitting in the waiting room of a dentist’s office about to undergo a quadruple root canal/wisdom tooth extraction. My mind was as open as the aperture of a pin hole camera. What was he going to do with my cell phone, place a very, long distance phone call to the dead? That’s not covered by my calling plan. |

| |

“...Let me just sort of tune in here. It’ll look like I’m sitting here with my eyes closed, but I’m getting information that I’ll come back and share with you, so bear with me for a few minutes.” |

| |

What was I doing in the living-room of “Intuitive Consultant” and psychic medium Stephen C. Robinson? I don’t believe in psychics, spirits, astrology, crystal balls, or prognosticating palms. I don’t even believe in God, Christianity, The United States, any traditional ideology or dogma. Often, I don’t even believe in myself, but I do believe in painting. I believe in painting. |

| |

“Oh I had this really strong vision...of um a group of spirit people working with you, and um I feel like they’re with you, not like they walk around following you as invisible people...” |

| |

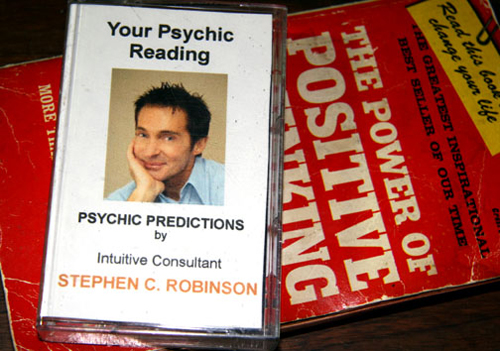

I came to Stephen C. Robinson’s well-furnished Chelsea apartment to speak to the dead. I selected him from the myriad of internet psychics because of his photograph. Immaculately groomed with plucked eyebrows and spiked hair, he cupped his puckish face with the palm of his hand. He was the antithesis of the psychic stereotype, a Gypsy woman with a bandanna tied around her head gazing quizzically into a cloudy crystal ball. His photograph looked like a soap opera star’s publicity photo. If he wasn’t a good psychic maybe he could act like he was. |

| |

His web site proclaimed in large letters surrounded by stars and moons, “Your future can be seen today. Professional sessions for today’s discriminating client. A Gifted Psychic Medium as seen on TV and Radio. In practice for over twenty-five years.” There was a list of “actual” testimonials by past clients who claimed that Stephen C. Robinson had helped them find lost broaches, predicted impossible pregnancies, and even communicated with dead relatives. I wanted to communicate with dead artists. |

| |

His assistant assured me in my telephone screening that if I brought good energy, a personal item that had always been in my possession, photos and reproductions of the paintings of the dead artists I wished to contact, and a credit card, Stephen C. Robinson could channel the energies of the spirits with whom I wanted to connect. |

| |

I brought eleven four by five photographs of deceased artists and writers. Most of them were self portraits in oil paintings and etchings. They were spread like a winning poker hand on the glass table in front of me. Something about their size reminded me of vacation snapshots of family and friends. Caspar David Friedrich, Hermann Hesse, Max Klinger, Edouard Manet, Heinrich Von Kleist, Charles Baudelaire, Eugene Delacroix, Walt Whitman, Jean Singer Sargent, and William Wordsworth stared up at us impatiently. |

| |

Soft music was playing in harmonic pastels, as aromatic candles flickered in the room. Stephen C. Robinson wore a slimly tailored dark-blue pin-stripe fashionable suit with a dark dress shirt. After the recent occult photography show at the Met, I expected him to be wearing a cape, turban, or at least an eccentric mustache. |

| |

The setting was more like the scene of a soap opera seduction than a seance. Displaying a mastery of dog training and theatrics Stephen C. Robinson abruptly interrupted me, got up out of his seat, and dimmed the lights. |

| |

“Painting is an act of implicit faith, try to have faith in this,” I thought to myself. As skeptical as I was, I vowed to participate in this encounter as sincerely as I could. In a sense, I communicate with the dead regularly. When a work of art affects me, I feel an intense dialogue with the artist. In his journal, Eugene Delacroix wrote, “Besides the pleasure of being praised, there is the thought of communicating with other souls capable of understanding one’s own, and thus one’s work becomes a meeting place for the souls of all men...Living in the minds of others is what is so intoxicating(Delacroix 42).” |

| |

When I am deeply engaged in a painting, I feel the artwork is consecrated. In the psychic vernacular, this may make a work of art a spiritual conduit capable of evading time, distance and death. Artists have always been described as alchemists and conjurers; is it possible they are spiritual mediums as well? |

| |

Stephen C. Robinson seemed to agree, “I feel like with some people and art that they may be mediums, and I don’t mean the material that they use. I mean mediums as in people who communicate with the dead...It’s said in emotion, and it’s said in intuition. It’s like it’s something that goes around the intellect. It is something that bypasses the intellect...there’s mediumship that’s connected to art, intuition. I feel like since you were a little kid you were selected for this, you were chosen for this...And I’m really feeling that your purpose, as in why you’re here on the planet, is to convey something that goes beyond everyday life, and transcends time. That’s your issue...to transcend time.” |

| |

I brought one more photo to that session, and Stephen C. Robinson was holding it as he spoke. It was a digital image of one of my own paintings, depicting American soldiers in Iraq sitting in a tan mud covered Humvee listening to a CD by the 80’s punk band The Misfits. The painting is called “Static Age.” There was no way he could have known or deduced this. Things were about to get interesting. |

| |

“I don’t want to impose my beliefs on you, but I do very strongly feel that there are very strong past life connections to art with you as well. Uh, I don’t feel like this is your first time around as an artist. Um, I feel like you’ve spent many lifetimes as an artist...I see something about um, like paintings that, and I don’t know a lot about art, paintings like Monet and Impressionists.” |

| |

I was an Impressionist? I came here to talk to Romantic artists. “Maybe I was Mary Cassat,” the cynic in me quipped. Next, I supposed he was going to tell me I was also an artist during the Renaissance, or some other popular period that someone who had only a basic knowledge of art would know. Twenty minutes later he added, “...you had a past life, and it was short, and I feel like it was during what was called the Middle Ages, you know during that time...the art may have been religious in nature.” |

| |

I was self-consciously aware that my opinion was swinging uncontrollably between the part of me that wanted believe in Stephen C. Robinson and another part of me that wanted to scream, “You’re a fucking charlatan!” and storm out. He prophesied that art would become my career, my life, my identity, that my art would take me to another dimension, that I would “unfold my consciousness” through my art. I realized how vulnerable I was, because this is the future I wanted so desperately, but I never asked him to tell me my future. |

| |

I already know it as if I am my own fortune teller. I will always make art, and it will always be a struggle. Maybe this is the seduction of psychic advisors, and why the practice is supplanting psychiatry and social work. Instead of paying to tell someone what you secretly know and don’t want to hear, you pay someone to tell you what you couldn’t possibly predict but secretly want to believe. |

| |

| “Enough of the future, what about the past?” I scolded myself, “Don’t forget why you’re here.” |

| |

Stephen C. Robinson began to shuffle the photographs of the artists and writers methodically. I thought of card tricks, sleight of hand, and prestidigitation. Was he going through the motions or could he see, hear, or feel something I couldn’t. I scoldedmyself for telling him which pictures were the most important to me. I didn’t want to give him any extra help in duping me. |

| |

“Who is this man?” he asked, holding up the picture of an etching of Caspar David Friedrich. It was the self-portrait of a young man with billowing curly sideburns that grew all the way down the sides of his face. |

| |

“I sense a warm energy from this man being directed towards you, and it’s coming through in the center of your back. Like something...pushing you forward to the canvas, and taking you to an altered state.” |

| |

I smiled because of an incident I had experienced with Friedrich the week before. I had been working on a painting that depicted a group of boys beating up another boy in a wintry graveyard. In the background, a group of druids in monk’s robes is running past a tall gothic tombstone to save the battered boy. I had just received Caspar David Friedrich and Romantic Painting by Charles Sala in the mail, and when I opened the book I was stunned. There was a picture of a painting by Ernst Ferdinand Oehme entitled “Procession in the Fog” in which a line of monks, in monk’s robes with hoods drawn, marches past a gothic tombstone almost identical to the one in my painting. The similarities were uncanny. I don’t think I have ever seen this painting before, and I don’t think I would have ever seen it if it weren’t for Caspar David Friedrich. |

| |

I handed Stephen C. Robinson the brochure from the 2004/2005 show “Comic Grotesque: Wit and Mockery in German Art, 1870-1940” at the Neue Gallery, in New York City. On the back of the pamphlet was a reproduction of a painting by Max Klinger from 1880 entitled “Der Pinkelnde Tod” or “Pissing Death.” This was the only picture by another artist that I had on display in my painting studio. This artist was the one of the main reasons I sought a spiritual medium. I wanted to contact Max Klinger because I felt such a strong affinity with the painting, and I wanted to know why. |

| |

“Pissing Death” depicts a skeleton holding a scythe in one hand urinating into a lake or ocean. The figure is dwarfed by a vast Romantic landscape rendered loosely in washes and thick paint, a palette of yellow ochre, burnt umber and raw sienna. I always remark that even though this painting is one hundred and twenty-six years old, it could have been made yesterday. The subject matter possess the wry wit of contemporary culture balanced with something grander, something ineffable. |

| |

| In anticipation of my appointment with Stephen C. Robinson I investigated the work of Max Klinger. |

| |

“Klinger was the modern artist par excellence. Modern not in the sense that is currently given to the word, but in the sense of a man of awareness who feels the heritage of centuries of art and thought, who sees clearly into the past, into the present and into himself(Klinger viii).” When I read this quote by Surrealist artist Giorgio De Chirico, I felt like Klinger embodied the type of artist that I wanted to become. My approach to painting, a type of figurative realism that reflects the seductive properties of oil paint, was referential to the long tradition of painting. |

| |

Painting for me has never been overshadowed by its’ antiquity, or what Gerald Marzorati, in his biography of painter Leon Golub A Painter of Darkness, describes as the “elegiac”. I believe painting remains a valid way to communicate contemporary ideas. The fact that I strongly identify with a painting over a century old seemed to reinforce this. |

| |

As I read more about Klinger and the early nineteenth-century German Romantic tradition that influenced him(Klinger xv), I realized that one of the things that drew me towards him and artists like Caspar David Friedrich, was the artist’s sense of Weltanschauung, or comprehensive world view, as reflected in their work. Weltanschauung is an ethical vision of the world, a set of principles, a creed. Klinger presented the banality of modern life through an ontological, existential, and sociological perspective. |

| |

Regarding Klinger’s conscience, J. Kirk T. Vanderhoe writes”...we might find here an archetypal ideological dilemma, between self-indulgent dreaming and the political responsibilities of critical analysis, set in a period of crisis in burgeoning capitalism(Klinger xvii).” As an artist, I strongly identify with this dilemma, and I feel that if one substituted “globalism” for “capitalism” it could describe an artist’s challenge today in 2008. |

| |

There was an elusive spirit to this work that also fascinated me. I was having trouble defining this essence until I encountered a description of German Romantic writer Heinrich Von Kleist in Charles Sala’s book, “His essays veered sharply away from objective reality to concentrate on the specifically human situation: deprived of paradise man lives in a circular dimension, ever in search of a new grace, which may be granted by the unconscious, a dream, or a new unfolding of the personality(Sala 76).” |

| |

In spite of Klinger’s subject matter in “Pissing Death,” the fantastical image of death as a living skeleton, the painting possessed grace. This was something I tried desperately to convey in my work. Stephen C. Robinson told me my consciousness was going to unfold throughout my life. Like Kleist’s description of an unfolding, did this mean I will achieve a “new grace” in my work? |

| |

When Stephen C. Robinson examined Klinger’s “Pissing Death” this is what he saw, “What I sense with this is just this feeling of compassion that I get with him, like my heart center is drawn into this, and um I’m feeling that...that level of energy is coming through to you. Not just from this, but from his spirit...that’s going to be part of the sublime experience for you, compassion.” |

| |

I had mentioned the sublime at the beginning of our session, as a characteristic that linked all the artists whose photos I had brought. The sublime was a crucial component of the Romantic’s philosophy. I thought back to an old high school art history aphorism, “The Romantics valued the Sublime over the beautiful.” I recently read Edmund Burke’s A Philosophical Enquiry Into the Sublime and Beautiful and was struck by the relation of terror to the sublime, but more specifically Burke’s etymological investigations of word terror. Throughout history the word has been associated with astonishment, admiration, reverence, and amazement(Burke 102). These words are all qualities of Romantic painting that I revere, but with an artist like Friedrich this sentiment is mainly derived from the grandeur of nature. My work, and possibly the work of Max Klinger, derives the sublime from everyday life. |

| |

When Steven C. Robinson spoke of compassion, I made an instant connection. As opposed to nature, compassion relates to humanism, man’s relation to man, society, the universe. I believe an existential investigation of the sublime is an essential contemporary function of art. I now believe this is an important exploration in my work, to illuminate the sublime through a compassionate depiction of the world as I experience it. |

| |

Stephen C. Robinson had made another psychic connection that he was unaware of. In researching Romanticism’s lineage/legacy, I frequently came across references to Edouard Manet. In Beth Archer Brombert’s, Rebel In a Frock Coat, she writes, “In Manet’s artistic lexicon sincerity was a key word. The text for the catalog of his private exhibition in 1867, presumed to have been written by him, contains this key word: ‘The artist does not say today, ‘Come and see flawless work,’ but ‘Come and see sincere work.’” |

| |

Compassion and sincerity are important moral precepts in my world view, and I enjoyed thinking about these ideas in relation to art making. One can’t be compassionate without sincerity. I thought of Manet when Stephen C. Robinson spoke of compassion. Bromberg continues, “The word sincere was not a neutral adjective at the time. As historian Philip Nord points out, ‘It is easy to forget the extent to which notions of sincerity were freighted with radical connotations.’ The word became a Republican shibboleth. ‘To claim for Manet[and] for the new art the mantle of sincerity was to elevate it into a challenge not just to the academic bombast but to a prevailing climate of reaction.’”

|

| |

I feel the word sincere is as radical an idea today as it was in the nineteenth-century. In rebellion against an inflated elitist art market that overvalues nihilistic artwork, to be a sincere artist one must disregard economics. To make art without any concern for money has again become a revolutionary idea. In conversations with fellow artists and friends one can’t even mention words like compassion or sincere without fear of being judged as sentimental, cheesy, or new age. An urbane vernacular without words like sincere is an impotent language incapable of communicating substantive emotion. An oligarchy of indifference must be overthrown. |

| |

I began to realize as the psychic reading progressed that I was no longer concerned with the validity of Stephen C. Robinson’s words. When I pressed him about Delacroix, he claimed to see the word “revolution.” Anyone with the slightest art education who has seen Delacroix’s painting “Liberty Leading the People” knows of the re-occuring theme of the French Revolution is his work. Anyone who is familiar with the Broadway musical Les Miserables might have even been able to fake it. |

| |

| I didn’t need a psychic. I was channeling Delacroix as I read his journals. I felt his presence as I painted that week, and he wasn’t whispering the word “revolution” from the great beyond. He was telling me about color and line and women and the desperate urge to be a good person and a great painter. When I looked at his self-portrait from 1837, I could hear the dead speak, “You who are withdrawn from eternity for so short a time, think of how precious these moments are(Delacroix 33).” |

| |

When Stephen C. Robinson claimed he could “psychometrize” a painting and see the artist through the work. I nearly laughed out loud. |

| |

But Stephen C. Robinson was offering me something more substantive and material than the psychic or the supernatural. He gave me affirmation that I was a proper heir to the legacy of artists whose work and beliefs I found meaningful, “There are paintings that you’re gonna paint that you have no knowledge of now, just amazing things you’re gonna do. And I feel this troop of spirit people and their collective energy are gonna work with you with this . Especially that one man with his hand behind your back pushing you forward. You’re really gonna feel that. It’s gonna be an amazing feeling.” |

| |

And he gave me a new provocative way of thinking and talking about my art, “There’s a merging with the canvas spiritually, and it’s like the creator and the object being created are merged into one, and that’s the element of time being lost. It’s like you’ve transcended that clock time...you’ve transcended time...that’s one of the symptoms of an altered state of consciousness, you have an altered perception of time. You called it the sublime, that’s it. It’s when your consciousness merges with the canvas. It becomes you. It’s like the spirit working with you, you, the canvas, are all one, and there’s just this turning of energy.” |

| |

I have begun to think about art beyond issues of aesthetics. Introducing sincere into my critical vocabulary, I feel it is an artist’s duty to think about the creative process in terms of morality. I’m not suggesting that an artist makes moralistic artwork, but that an artist treats the process of making art with compassion, openness, honesty, sincerity, with qualities of grace. Grappling with these existential concerns, an artist will make works of art that truly resonate. In his Letters on Cezanne, Rainer Maria Rilke writes, “Today I went to see his pictures again; it’s remarkable what a surrounding they create. Without looking at a particular one, standing in the middle between the two rooms, one feels their presence drawing together into a colossal reality. As if these colors could heal indecision once and for all. The good conscience of these, reds, these blues, their simple truthfulness, it educates you; and if you stand among them as ready as possible, you get the impression they are doing something for you(rilke 46).” |

| |

When one stands before a painting the artist has fully considered, when one stands before a painting where the artist was so engrossed in the process that he or she transcended time, when one stands before a painting and a sense of grace is felt, this is the sublime. |

| |

| Stephen C. Robinson told me my fortune that day. He said I would live to be in my nineties, a great teacher, and artist. Even though I was aware that I was paying him to tell me these things, and even though I didn’t really believe he could tell the future, I know that if I stay true to this artist’s life, I will live in my work a lot longer then I ever thought possible. |

| |

| |

| |

|

Brombert, Beth Archer. Rebel In A Frock Coat. Chicago: The University of Chicago,Press Ltd., 1996.

Burke, Edmund. A Philosophical Enquiry into the Sublime and Beautiful. Edited by David Womersly. New York: Penguin Books, 2004.

Delacroix, Eugene. The Journal of Eugene Delacroix. Edited by Hubert Wellington. Translated by Lucy Norton. Phaidon Press, Ltd., 2004.

Hesse, Hermann. Narcissus And Goldmund. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1999.

Hughes, Robert. Goya. New York: Random House Inc., 2004.

Klinger, Max. Graphic Works of Max Klinger. Introduction and notes by J. Kirk T. Vanderhoe, with Elizabeth Streicher. New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1977.

Marzorati, Gerald. A Painter of Darkness: Leon Golub and Our Times. Penguin Books, 1990.

Neret, Gilles. Delacroix: 1798-1863 The Prince of Romanticism. Taschen, 2004.

Rilke, Rainer Maria. Letters On Cezanne. Translated by Joel Agee. New York: Northpoint Press, 2002.

Sala, Charles, Caspar David Friedrich and Romantic Painting. Editors Jean-Claude Dubost and Jean Francois Gonthier. Paris: Finest S.A./ Editions Pierre Terrail, 1993.

Von Kleist, Heinrich. Selected Writings. Edited and Translated by David Constantine. Hackett Publishing Company, Inc., 1997.

Wordsworth, William. Selected Poems. Edited by Stephen Gill. New York: Penguin Books, 2004. |

| |

|